Forest Voices: ‘A new relationship with forests will cool down the planet.’

Silvio Netto is helping to coordinate the restoration of 2,000 hectares of forest following the devastating impact of two mining disasters in Brazil. But reforestation alone is not enough. He says the way the environment is managed must radically change – socially, economically and politically – to ensure a sustainable future.

By Molly Millar

From Chatham House

‘We need the trees.’

‘We need clean water and clean air.’

‘We need biodiversity.’

‘We need a good place to live.’

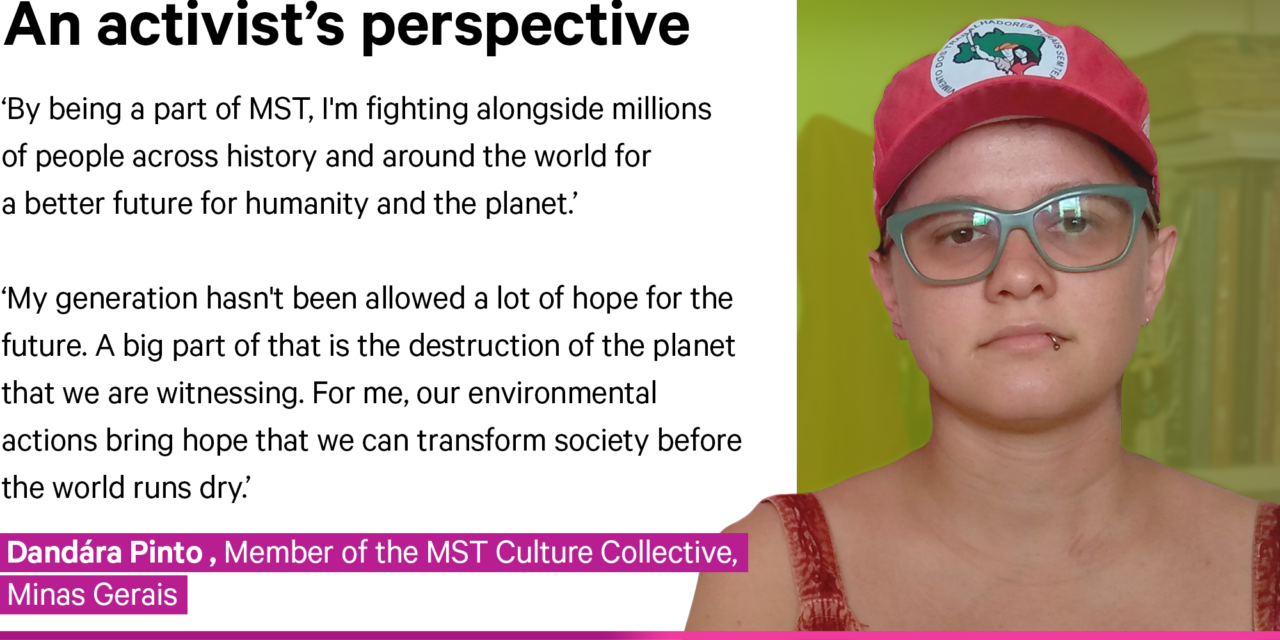

Internationally, the MST is one of 182 organizations around the world fighting for agrarian reform and the rights of 200 million rural people as part of La Via Campesina.

‘It’s in the very nature of rural people to protect the environment because we live on the land,’ says Silvio.

Within Brazil, MST’s mass social movement seeks to win the right for families to live and farm on unproductive land held by big landowners, banks or the state. It estimates that it has helped 350,000 families to establish legally recognized settlements. Forest conservation and restoration is central to the organization’s aims, and last year, it launched an initiative to plant 100 million trees across Brazil over the coming decade.

Dams and devastation

Silvio lives in Minas Gerais, a state in the southeast of Brazil. In November 2015, a mining disaster near the city of Mariana led to the collapse of the Fundão dam. The collapse released a wave of toxic mud, killing 19 people, and destroying more than 1,400 hectares of forest. 50 million cubic metres of iron-ore residue also surged into the Rio Doce river, contaminating local drinking supplies.

The dam was run by Samarco Mineração – a joint venture owned by two mining giants, Brazilian multinational, Vale, and the Anglo-Australian conglomerate, BHP.

Four years later, a second dam breach, attributed to Brazil’s biggest mining company Vale, occurred near the city of Brumadinho, killing 270 people.

‘People in mining territories – especially where the crimes happened in Brumadinho and Mariana – are in a state of despair,’ explains Silvio.

A commitment to restore

By way of reparations, the Brazilian government established a legal commitment in 2016 with Samarco Mineração under which the company is supporting efforts to restore the land and rebuild the livelihoods of those in the affected communities.

The Renova Foundation, the non-profit organization set up to implement these reparations, is working to restore a total of 40,000 hectares by 2027. In the Rio Doce river basin – the area most affected by the collapse of the dams – Renova has been funding the MST which aims to reforest over 2,000 hectares in the area over the next 10 years.

Restoring the degraded land can both improve communities’ livelihoods and have substantial environmental benefits, explains Miguel Calmon, senior consultant at the World Resources Institute in Brazil. It helps to improve water quality, soil health and biodiversity, generate jobs and income and contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

‘If you restore the land you can really increase the resilience of those landscapes and be more prepared to face the consequences of climate change that’s already happening in many places in Brazil,’ he says.

On the land, for the land

MST has aligned its response to the disasters with its Popular Agrarian Reform programme – a nationwide project with the goal of putting rural communities in control of their land and allowing them to reap the benefits of forest restoration and food production where they live.

‘Our solution is to restore the destroyed areas, maintain the forest areas that still exist and, at the same time, produce food in harmony with nature,’ Silvio says.

Both environmental issues and social transformation go hand in hand for these rural communities. ‘The true guardians of biodiversity and nature are the people that live on the land, from the land, and for the land,’ says Silvio.

‘That’s why access to the land for rural communities is so necessary for environmental preservation.’

Involving local people in restoration and reforestation efforts is one of the ‘golden rules’ for successful tree planting according to a recent review led by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Botanic Gardens Conservation International.

‘Restoration, tree planting and reforestation are long-term initiatives. Time is the best fertilizer you have for getting environmental benefits. It takes persistence so you must have local people as a partner,’ explains Professor Pedro Brancalion of the University of São Paulo, one of the article’s authors.

‘Lack of appropriate engagement with local people can lead to a reforestation project being completely lost or abandoned and never deliver the benefits that are initially targeted for that area.’

Training in agroforestry systems – a practice which combines best agricultural and forestry techniques – is also being provided to people in the area.

The MST’s local Ho Chi Minh seedling nursery, for example, provides seeds for planting across the state, and also serves a dual purpose as a centre for environmental education.

‘There’s a lot of technical aspects behind restoration especially when you’re talking about agroforestry systems. There’s certainly a need for technical assistance,’ says Calmon.

But government programmes and support are often limited so knowledge sharing among farmers can be crucial in filling in the gaps.

As well as restoring the land, the MST is showing an alternate path for people’s relationship to the natural world and, in the face of climate change, Silvio argues that this is crucial.

‘What’s going to cool down the planet is a new relationship with forests and nature and a new standard of food production,’ he says.

One aspect of this is ensuring that food production doesn’t damage the environment which they aim to achieve by introducing a new system of agroecology. Indeed, the organization is seeking to support communities in growing, distributing and consuming food using sustainable methods, in line with the UN-recognized concept of food sovereignty that calls for the right of people to freely define their own food and agricultural policies.

Helping communities to organize cooperatively is another priority for MST since working together as a community can bring economic benefits to farmers. ‘Family farmers already spend their limited time producing food, so by organizing themselves through cooperatives, they can market their products together and make more money,’ Calmon says.

‘In a situation such as Brazil’s, having easy access to food is a very big deal and helps families to live with dignity,’ adds Silvio. ‘And when the food that we grow on our land gets to the city, it will feed our friends, our family, people like us. Poor people and working people. So it’s important for us that it is healthy.’

Learning lessons

While restoring the land impacted by mining disasters can benefit both the environment and the welfare of rural communities, much has been permanently lost in the initial destruction, explains Professor Brancalion.

‘When we talk about deforestation, we’re talking about losing huge trees that have grown over decades. And when we plant trees, we are planting baby trees and they may take decades to centuries to sequester large amounts of carbon.’

Preventing deforestation will always be more impactful than reforestation, he adds, and restoration needs to be done in the right way. ‘In many cases here in Brazil, seedlings can die because of hot weather, drought, competition, because of many different factors. It doesn’t matter how many trees you plant – what really matters is if you succeed in establishing a diverse forest ecosystem.’

For example, initial restoration efforts by Renova used exotic tree species, rather than native species, breaking one of the scientists’ ‘golden rules’ for successful tree planting – and only 50 per cent of the seedlings planted survived.

This links to another of the ‘golden rules’, the importance of learning by doing, which requires regular monitoring and the ability to adapt when necessary. Indeed, when done right, it can unlock wider impacts to help mitigate the challenges of climate change.

‘Degraded lands and forests can be converted back to productive and functional lands, not only for producing food through agroforestry systems, but also for generating important ecosystem services and reducing risks of flooding and drought that result from climate change,’ says Calmon.

Changing our relationship with the land

Silvio argues that by putting marginalized rural communities and the natural world at the centre of its reform, agroforestry can act as an alternative model for food production that, if expanded, could alter the course of the world’s journey away from potential climate collapse.

‘Many people and organizations throughout history have fought for another society, for social transformation, another way of life. And we are convinced that this other way of living has to change our relationship with the land, with nature and the environment,’ he says.

‘Brazil can be a superpower on sustainable food production and conservation. We just need to bring them together. And I think we are seeing more and more examples of how we can do that,’ adds Calmon.

‘But we definitely need to mobilize enough resources to make this happen, at scale and fast, because the climate crisis needs ambitious action. That’s why it’s important to work with every side of the political spectrum – whether that’s private corporations or local communities.’

Tragedies such as the mining disasters in Minas Gerais highlight the damage corporations can impose on the country’s land and the lives of its people. But the MST’s commitment to restoration shows another path where forestry and food production initiatives are led by rural people working to ensure both they, and the natural world, thrive.

‘The logic of big business – mining or agriculture – that owns the biggest part of the lands of Brazil is industrial logic that wants profit above all else,’ says Silvio.

‘On the other hand, under our logic, the logic of rural people, and the logic of agrarian reform, it is the pursuit of life.’

Key points for COP26

- Restoration of large areas of degraded land around the world is critically important for addressing climate change through both increasing tree cover and establishing resilient land-use systems.

- The environmental and social outcomes of reforestation and restoration are intertwined. Thus, a wide range of benefits must be sought, for ecosystem services and rural livelihoods.

- The most effective approach to restoring land is by putting local people at the centre of such efforts – they not only have knowledge and expertise about their lands but can provide the long-term management required. This can present opportunities to explore more equitable models of land-use.

- Restoration initiatives need to build in effective monitoring so that they can be adapted accordingly. Adequate resources are also needed for training and capacity-building.

- Reforestation and restoration take time and commitment. The prevention of deforestation and environmental damage will always be better than restoration for which the effective regulation, licensing and monitoring of land-use is fundamental.

About the series

This new set of stories aims to draw attention to the critical importance of good forest governance for achieving global commitments on biodiversity, climate change and poverty eradication. Through personal perspectives on a variety of approaches from around the world, the series seeks to highlight some of the lessons learned so far and what further action will be needed at the UN’s COP26 climate conference in November 2021 and beyond.

*Graphics by Alex Sommers. Direction by Simon Davis.